Understanding Delusions

Delusions show what happens when our inner world drifts from reality. Reflect on when your senses misled you.

Key Takeaways:

- Delusions are firmly-held, false beliefs, often resistant to outside evidence and detached from cultural norms.

- The brain is a prediction machine, using errors between expectation and perception to update understanding.

- Delusions emerge when prediction errors fail, allowing inner beliefs to drift away from external reality.

- Common delusions include persecution, reference, and telepathy, though rare forms like Cotard or Capgras syndromes also occur.

- Delusions can sometimes provide comfort, reducing anxiety or easing adjustment to illness, even if inaccurate.

Delusion has been a topic of scientific study since before the study of the mind became a science. The Diagnostic and Statistical Model of Mental Disorders, the bible of modern psychiatry and clinical psychology, defines delusions as firmly-held, untrue beliefs about the external world that are rejected by one’s culture.

Your brain is essentially a prediction machine. It notices patterns in the data from your senses and forms an expectation about the future. When you experience something new, your brain compares what you’re perceiving right now to the expectation you’d already formed from past experience. When “what you see” and “what you expected to see” don’t match, parts of your brain broadcast a signal that there was a mismatch. This prediction error helps you learn new things, and modify your internal conceptions to match the external world. But, if you fail to generate prediction errors, you can’t tell when your inner sense of the world is off, and so you can drift farther and farther from reality.

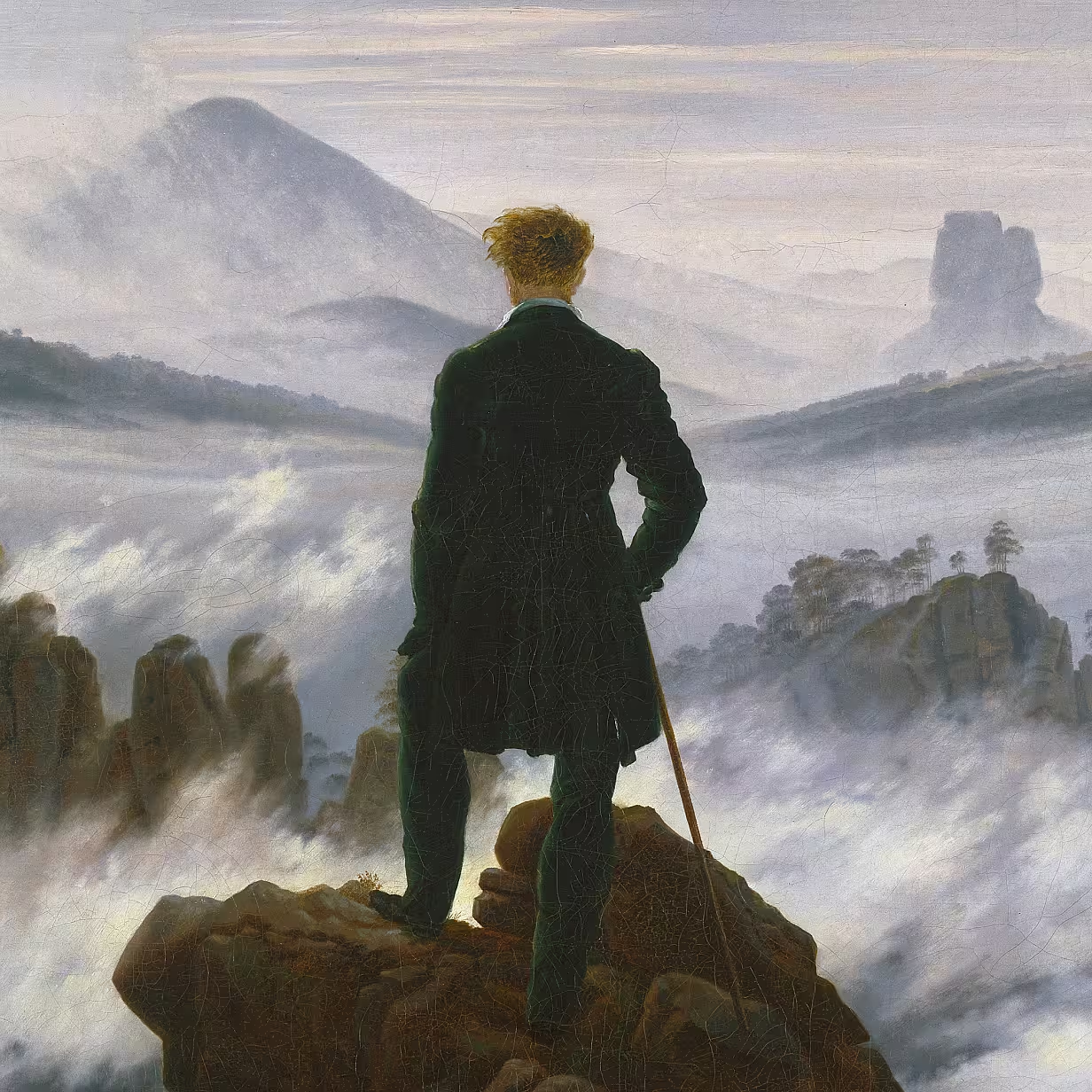

"The paintings of gibbons by Chinese monk-painter Muqi (active ca. 1250–80) were treasured by Japanese Zen monks. In these screens by Japanese Zen monk-artist Sesson, which represent an interpretation of Muqi's style, gibbons try to grasp the moon's reflection in the water below which in Zen, signifies the delusions of the unawakened mind. Image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Delusions can be incredibly idiosyncratic.

Novice psychiatrists and neurologists can make a name for themselves and establish their careers by describing (and naming) a bizarre new delusion observed in one or a few patients. One fascinating delusion is zoanthropy, in which patients have the delusional belief that they are turning into an animal, or in some cases that they are already an animal. Some patients will argue for years that they are in fact a rabbit or a cat, and no information from the external world can modify that belief. Wolf transformation delusions (lycanthropy) are the most common3. Other delusions might take the form of believing one’s limbs are under the control of some external force (Alien Hand Syndrome), that one’s body parts, blood, or organs have been lost or that one’s soul is lost or dead (Cotard Syndrome), or that a loved one has been replaced with an imposter (Capgras Syndrome).

Despite this heterogeneity, in some groups, delusions do tend to fall into predictable patterns. Anybody who has worked with schizophrenia patients will be struck by how people from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds nonetheless exhibit common patterns in their delusions. Delusions of reference (believing random events in the world have a personal significance, like thinking that the lyrics of a song on the radio are about you) and persecution (believing the government or some other shadowy force is pursuing you) are the most frequent in patients4, though telepathy beliefs (that you can read others’ thoughts or they can read yours) are also common.

Repoussé "masks" were intended for use in the creation of lifelike effigies of the gods. Chamunda, symbolizing delusion and death, was used for processional use, often carried by devotees during festivals. Image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

It seems pretty self-evident that delusions are a bad thing. If your inner world has become unmoored from actual reality, that would seem like a problem in need of fixing. But can delusions actually be beneficial?

Researchers at the University of Birmingham recently argued that, in certain circumstances, they can. Many delusions cause distress (most people who think the government is conspiring against them are not happy about it!), but occasionally they’re a source of comfort. A paralyzed person with anosognosia will deny that they’re paralyzed. They’ll make claims like “I am moving my arm” while their arm is paralyzed or “I can climb stairs but I’m slow” despite not having functional legs5. Often, they will invent elaborate stories about why they just don’t feel like moving when asked. As far as any doctor can tell, the patients are not lying; they actually seem to believe they’re not paralyzed. Not surprisingly, they exhibit much less anxiety and other negative emotions about their condition than patients with an accurate view of their physical condition. Anecdotally, this short-term coping mechanism seems to be useful for the patients, as it lets them adjust slowly to new realities of life. Less dramatic delusions, like a sense of personal grandeur or wild overconfidence, can even be biologically useful in a potentially Darwinian sense, as confidence is a trait highly valued in the dating world.

Think about times when what you saw/heard/smelled/tasted didn't align with what you expected.

Was it confusing? Exciting? Freeing?

References

1 American Psychiatric Association. (2013). DSM-V: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th Rev ed.). Washington, DC: APA.

2 Corlett, P R et al. “Toward a neurobiology of delusions.” Progress in neurobiology vol. 92,3 (2010): 345-69. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.06.007.

3 Guessoum, Sélim Benjamin et al. “Clinical Lycanthropy, Neurobiology, Culture: A Systematic Review.” Frontiers in psychiatry vol. 12 718101. 11 Oct. 2021, doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.718101.

4 Bhuyan, D. & Chaudhury, P. K. (2016, May). Nature and types of delusion in schizophrenia and mania–is there a difference? IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences. 15(5), pp 01-06.

5 Bortolotti, L. The epistemic innocence of motivated delusions. Consciousness and Cognition (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2014.10.005.

Build your practice of daily discovery.

7 days free.

Sign up for more bites of curiosity in your inbox.

Ongoing discoveries, reflections, and app updates. Thoughtful ways to grow with us.

.svg)